New Mexico, (1880 - present)

For most of your tenure as Bishop, you likely knew me as Galisteo Junction. Before that—long before your time—I was known as El Rancho de Nuestra Señora de la Luz (“The Ranch of Our Lady of Light”)—a grant of trust from the faraway Spanish Crown to Diego Antonio Baca of the Baca family—in a time when my first caretakers—the Tewa Pueblo and Tano peoples—grew crops in my soil but didn’t consider ownership of land the same way European settlers did when they arrived.

Oh, how I miss those times.

When the Baca family left my care to the Catholic diocese, I came under various administrators, including you—though to my recollection, you never came to see me.

And maybe that’s what I’ve always wanted to ask you, Jean-Baptiste Lamy—why not once? Why not a glance, a step, a blessing?

They said I was named in your honor. But what does that mean, when the man himself never walks your streets?

You made your home in Santa Fe. You got stone cathedrals and stained glass and men in pressed collars to say your name from pulpits. They built you a bronze statue—a funnily ironic tribute for a priest—a graven image. Your bronze likeness stands proudly outside the basilica, under whose floorboards your bones have resided since the day of your death—your eyes cast upward, unaware of the statued robes just outside, caught in a wind that never blows here.

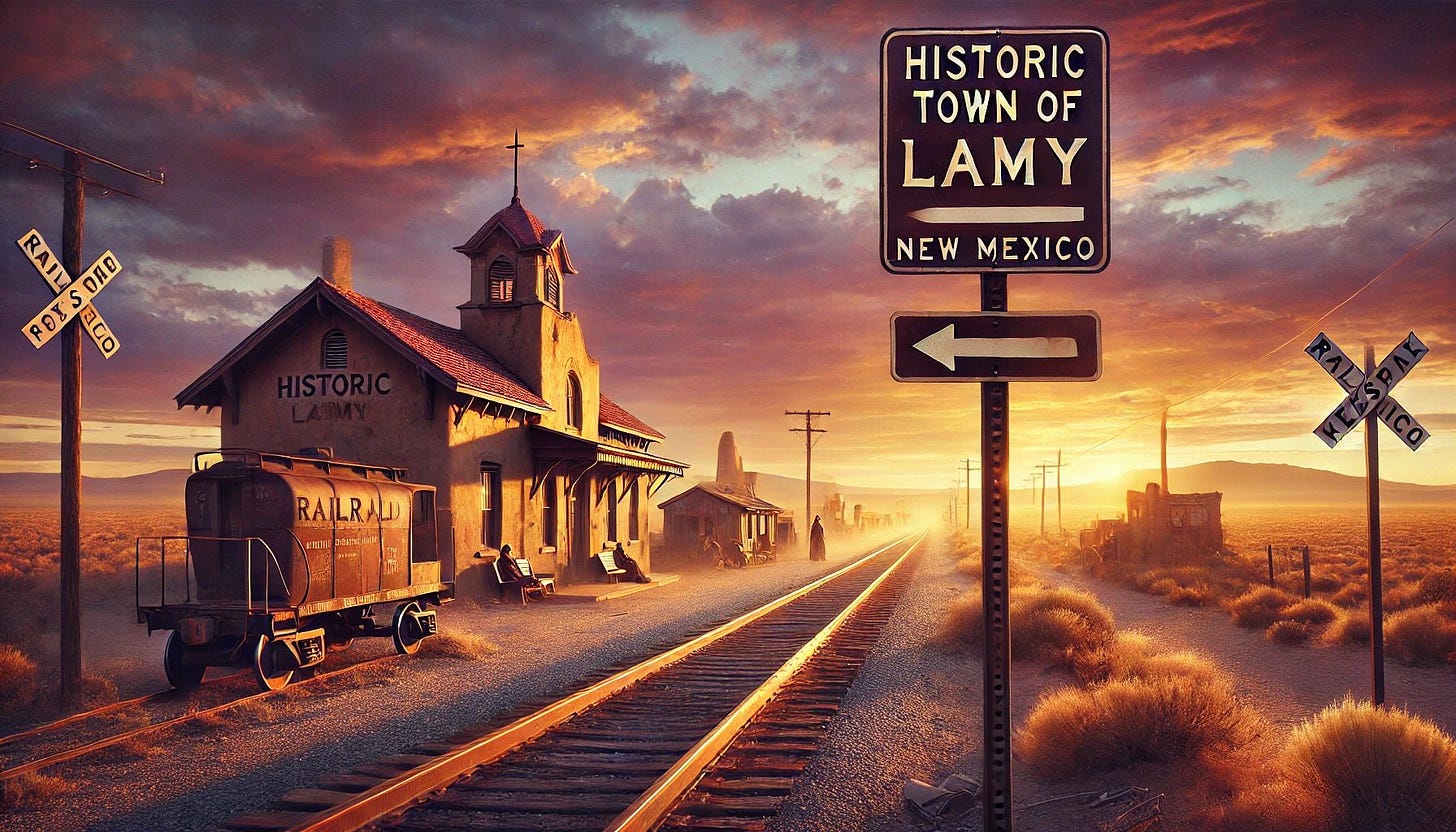

I was carved out of necessity. In 1880, when the Santa Fe Trail ran into terrain too stubborn to blast through, they sent the tracks south—to where I was waiting in the dust, not yet a town, not even a plan.

I was built with a bend in the rails and hope in the timbers. A depot. A saloon. A church with no priest.

When the railroad came, a deal was struck and they gave me your last name and nothing more. Lamy. And ever since, I have carried the weight of your name in railroad spikes and cracked adobe.

And I tried—God help me, I have tried—to live up to it. I have carefully sheltered and held close those who came here and, in turn, cared for me.

They say a town grows like a child when someone’s watching. I had to raise myself.

Still, I boomed.

Three hundred hearts by 1930. I fed them on rail work and whiskey and desert light. The Legal Tender Saloon was gospel on Saturday nights—guitars strumming over the clatter of glass. My depot shined like a silver tooth, red tile roof catching fire in the sunset.

And I kept secrets. Oh, Jean-Baptiste, I kept them tight.

From heaven, you’ve heard of the Manhattan Project, I’m sure. The boys bound for Los Alamos? Most of them came through me. Young, nervous, brilliant. One stepped off the Super Chief in ’43—bent over a telegram and trembling. His name was Klaus Fuchs. I didn’t know it then, but he’d pass secrets to the Soviets before the war was done. He smoked two cigarettes on my platform, crushing them into my soil with the heel of his boot before he disappeared into the back of a waiting truck.

I never told. I couldn’t.

Dorothy McKibbin never passed through my depot—her office was at 109 East Palace, up in Santa Fe—but the men she guided came through my bones. My rails hummed with history nobody dared write down.

And when it all slowed—when the trains stopped coming and the town shrank to a whisper—they nearly shut me down.

The depot roof sagged. The bell cracked. The Legal Tender was shuttered and filled with pigeons. Weeds crawled through floorboards. Old men stopped coming. The silence set in like rust.

I almost died—as all towns do eventually. The bulldozers were ready. I thought I was done for.

But then came Judy—a local girl with paint on her jeans and wild hair. Judy Chicago. She bought the old saloon in the ’70s and said, “Places like this shouldn’t be erased.”

She saved me.

She threw open the doors and brought music back. Art. Poetry. She lit the rooms with neon and stubbornness. People started coming again—not many, but enough. And I started breathing again.

You should have seen her!

You should have seen the boy who buried a time capsule under the chapel. He was twelve. Said he was tired of places disappearing. Left a note inside: This town mattered. Please remember.

You never saw Georgia O’Keeffe walk past me once, quiet as fog, sketchbook tucked under her arm. She didn’t stop. But I felt her glance.

Even the quiet ones matter.

Even the forgotten ones carry history like marrow.

I’ve kept your name, Jean-Baptiste. Even when no one comes to speak it. Even when Santa Fe raised your statue and I got nothing but a tiny brown road sign that tourists squint at from their windows—a faded strip of aluminum with white letters and arrows on the side of the interstate that says: Historic Town of Lamy.

I don’t have basilicas or bishops. I have floorboards that remember every bootstep. I have dust that’s been blessed by accidents and intentions.

And still I whisper your name—not because I need anything from you. Not anymore.

But because this name—as much as all the others I have worn through the years—is mine now. Borrowed, but well earned.

My name is Lamy.

And like the 200 or so souls who call me home today, I’ve worn the name you left me well.

I really like this story.....