I am dying.

Not in theory. Not like the way you mean when you say someone’s wasting away.

No—this is the real thing. I feel the weight of it, heavy and familiar, like the winter coats we used to patch in Raleigh with string and prayer. Death is not a stranger to me. It is an old companion, walking a half-step behind for more than a century. And now it is beside me.

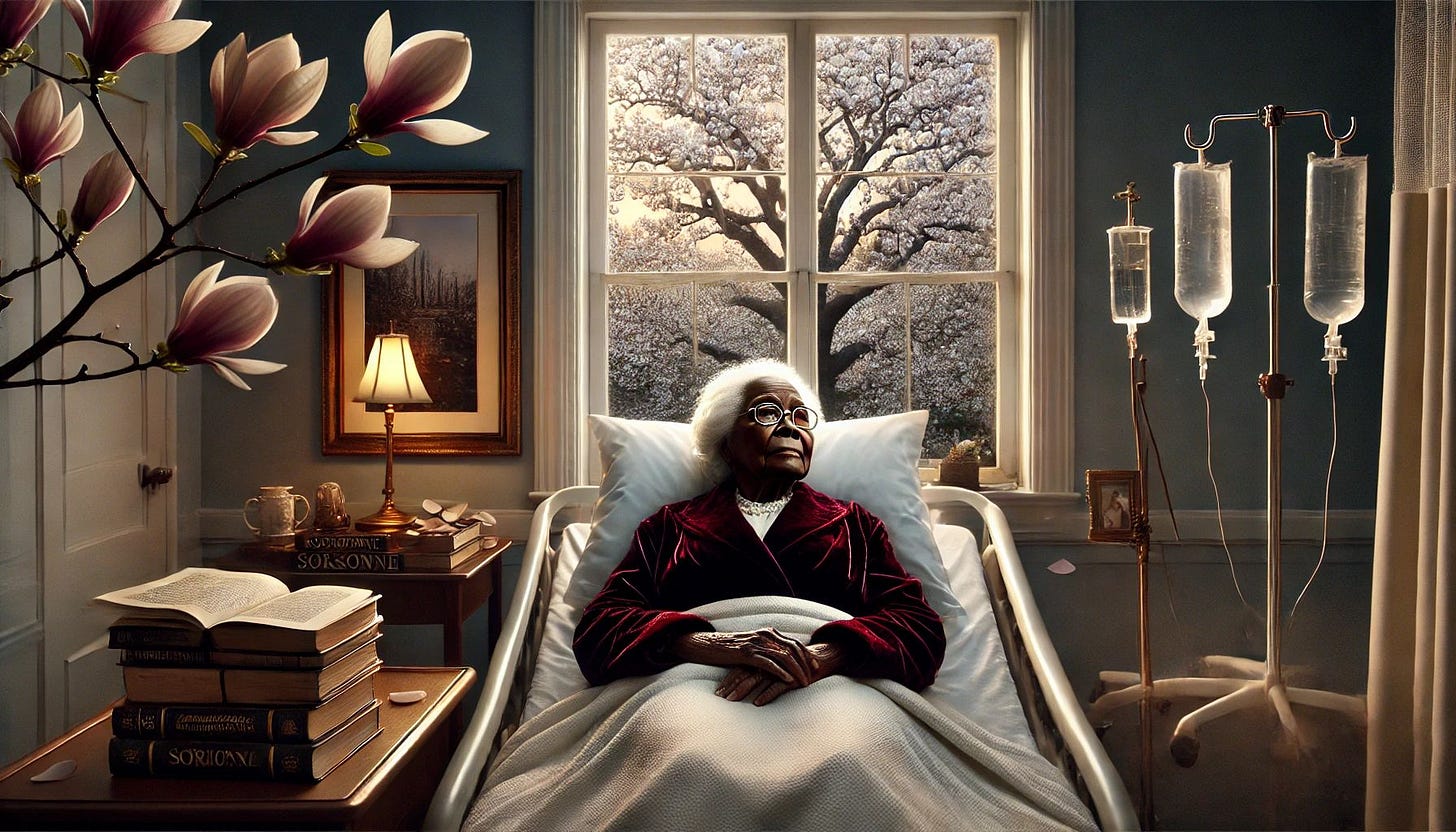

I hear the nurse’s shoes in the hallway—rubber soles on waxed tile, a rhythm I’ve come to know. They speak softly outside my door. They always do now. Like I might break if they say my name too loud.

But they don’t say my name. Not anymore. I’ve outlived it. Outlived nearly everything. I am a ghost wrapped in skin, a mind that refuses to bow even as the body caves in.

Still, I wait.

Because I have something left to say. And while breath still lingers in this chest, it will find its way into words.

It’s true what they say about your life flashing before your eyes at the end. And after 105 years, I guess it may take a while to play that film. I was born before film, you know—before a lot of things—but not before men had decided—at least on paper—that owning people was no longer alright.

The smell comes first in my memories—this film in my mind of my life. Tobacco, kerosene, and the sweet damp of the Carolina earth. I am five again, curled at my mother’s feet while she scrubs laundry against a stone basin. Her hands are cracked, stained, strong.

She is strong.

She doesn’t speak much—only when it matters. But she sings. Hums. Moans out spirituals with eyes closed and a jaw tight like she’s holding back a flood.

I don’t know then what she survived to become mine. I don’t know the name of the man who owned her, or the other one—my father—who never came calling. But I know her love.

It is quiet. Fierce. Absolute.

I was born into bondage but raised in resistance.

I feel a thread tug. It pulls me forward. Years pass in the blink of an old eye.

Saint Augustine’s School. I am nine, trembling in a wooden pew, feet dangling, eyes wide. I am free now. The grown-ups had a great big war to decide that. It ended just two years ago—right before they killed the president—President Lincoln. They killed another just last year—President Kennedy. Six presidents died while I have lived—four murdered, two claimed by illness. The world kept turning.

I didn’t pay too much attention to all that, though. I never cared for politics. I cared about learning. And for me there can only be one word to describe my life’s true love—where so much of the learning came from. I remember arriving at Saint Augustine’s, expected to learn quietly, gratefully—and my amazement at seeing so many in one place. Of course, as I would later tell my students, my greatest joy in life was found in these glorious little blocks of knowledge—books! Marvelous things! What would my life have been without them?

I can still smell them in my mind’s nostrils—the way I did when I was nine years old. They smell like old trees and oil. They weigh more than I do.

Just the thought of them puts me back there.

I clutch a primer in one hand and a Bible in the other. The boys learn Greek and Latin. The girls learn to pour tea and sew. I ask why. A teacher narrows her eyes, tells me I should be grateful to be educated at all.

I swallow the bitterness.

Then I sit in the back of the boys’ classroom—quiet, unnoticed. And I learn.

I learn until I outgrow their expectations.

My mouth tastes of metal now. The body sours near the end. But the mind—ah, it sharpens.

I see Oberlin. Ohio cold wraps around me like defiance. The air bites. The wind howls through coats never meant for girls like me. But I hold my head high.

In the classroom, I speak when not spoken to. I answer when challenged. I debate professors. One man calls me “uppity.” I smile. The word tastes like victory.

Mathematics bends for me. Languages open like doorways. I find truth in the logic. Power in clarity.

They said women shouldn’t study higher subjects. They said negro girls should be thankful to even be allowed to sit here and learn.

But I didn’t come to just sit and learn.

I came to rise.

Now I feel hands on mine—cool, gloved. The nurse again. She adjusts the blanket, not knowing I am far away.

I am in Washington. The war has ended but the battle never has.

M Street High School. My cathedral. I take it like a general takes the field.

I stand before my students—tall, proud, relentless.

“Read as if the world depended on it,” I tell them.

It does.

I teach Latin, literature, logic. I demand excellence. They say I expect too much. That I am too strict. That I frighten the white school board.

Good.

Let them tremble before Black minds on fire.

I blink. The ceiling comes back into view. Pale. Featureless. A canvas I refuse to leave blank.

There’s a photo on the table beside me. I can’t turn my head, but I remember. My foster son placed it there weeks ago.

It’s me, in Paris. Sixty-five years old. I am the fourth Black American woman to earn a Ph.D. At sixty-five, folks were already counting me out. But they had been counting me out since the day I was born. Truth is, I was just getting started.

The Sorbonne’s columns rise behind me. I wear my best coat, the one with the velvet collar. My thesis—defended in French—rests in my satchel. They questioned my credentials, my intellect, my audacity.

I gave them no choice but to accept me.

A Negro woman, alone, uninvited—and undeniable.

My doctorate is not a symbol. It is a scar.

Earned. Bled for. Worn with pride.

My chest burns. I cough, but no sound comes. My lungs are rust. The nurse returns and whispers, “Almost time.”

She has no idea.

Time has always been mine. I stole it from every man who tried to keep me in place.

They tried to bury me in silence. I answered with thunder.

I remember the letters.

Thousands of them.

Former students. Activists. Women who walked into classrooms with bowed heads and left ready to defy gravity.

One wrote:

“You didn’t just teach me facts. You taught me I was not furniture.”

Another:

“I used your lessons to raise my children. Now they’re raising hell.”

I saved every one.

They were my wages. My proof. My immortality.

I feel the end now. A tightness, low and final.

But still I have one more memory to unearth.

A church basement. No windows. Just gaslight and dust. My students are waitresses, janitors, Pullman porters. We sit in a circle. I hold a copy of The Republic. I pass it around.

We read. Slowly. Together.

I ask, “What is justice?”

They answer with stories. With scars. With laughter so rich it echoes for days.

That was my revolution. My rebellion.

Teaching the unseen how to see themselves.

The window is open. I hadn’t noticed. The breeze smells of rain on stone. And magnolia.

I haven’t seen a magnolia tree in years.

I think of him now. My husband.

He was kind.

We had little time. But it was enough to know love wasn’t always sharp-edged. He held my hand during my first year at M Street. Listened to me rant. Let me rage without shrinking.

He died before the dream bloomed.

I carried it for both of us.

Now the ceiling fades. I see the sky. And beyond that, something I can’t name.

Not heaven. Not peace.

Something quieter. Wiser.

Still.

But before I cross, I will leave you this:

There is no freedom without thought.

No change without defiance.

No future without women who remember who they are.

I was born with an enslaved body but a free heart. I seized every opportunity to learn with both hands. Every opportunity to teach with the same.

I was 62 years old before I could vote. I was 96 when the Supreme Court said segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. Ninety-nine when the Little Rock Nine were escorted to school by military guard. I was 102 years old when Ruby Bridges went to school under the watchful eye of U.S. Marshals and a television audience. I think I must have been 82 or 83 the first time I ever saw one of those. My, how this world has changed.

Education was a struggle. Life was a struggle. But do not weep for me. My life has been a good one, because unlike so many, I chose to live mine. To live. To love. To learn. To teach. Do not weep for me. Weep for those who didn’t. Then, perhaps—pick up a book.

Open your mouth.

Build a classroom in the ruins—in the places society neglects or restrains entrance.

Then—teach. Continue to learn. Teach some more. Learn some more. For that—that is the essence of a life lived well.

And I hasten to say—as I haven’t much time—that mine has been lived well. Very well.

I exhale.

It is not surrender.

It’s not even death like I suspected. Not really.

It feels more like—oh, yes. Yes, indeed. I stand proud. For it is graduation.

Author’s Note

This story is a fictionalized meditation on the final hours of a woman whose name deserves to be shouted from every classroom, every courthouse, and every whisper of justice: Anna Julia Haywood Cooper. While the events and memories depicted are drawn from the known facts of her life, they have been reimagined through a first-person lens to honor not just her biography but her essence—her intellect, resilience, rage, and grace. She was not merely a witness to history; she was its architect. Born into slavery, she became a scholar, an educator, a leader, and a voice—clear and unyielding—insisting that Black women’s minds were not just worthy of development, but essential to liberation.

Cooper is not remembered for being the first Black woman to do any one thing. She is remembered because she did everything, and she did it in a time designed to stop her at every turn. That makes her not just a pioneer, but a phenomenon. She stood at the intersection of race and gender, demanding visibility long before we had words like “intersectionality” to name the battle. Her life is a testament to the quiet power of persistence and the radical act of educating those the world tries to silence. Anna Julia Haywood Cooper was not only a giant of Black intellectual history—she was, and remains, one of the great feminists of any era.

I loved this story....