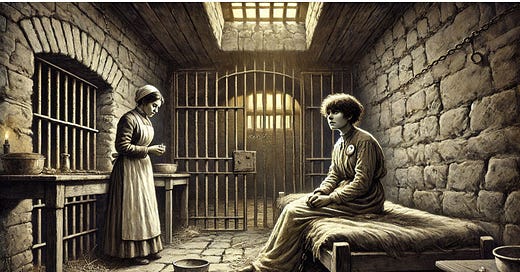

Occoquan Workhouse, November 1917

I am not meant to speak to her.

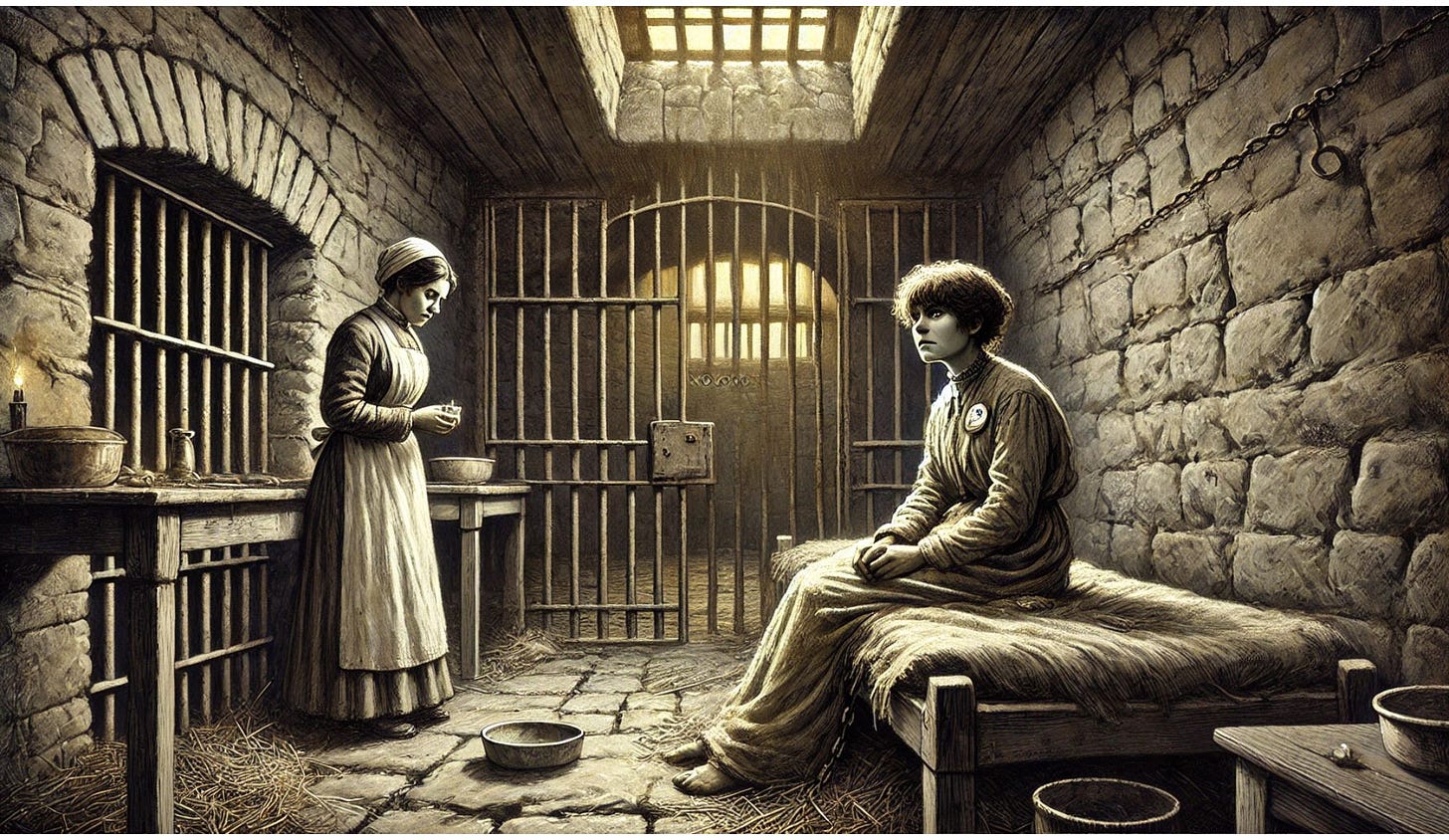

“She’s not a patient,” the doctor says. “She’s a protestor.” He points at his clipboard—the list of all the women they arrested at the White House gates. “She’s their leader,” he says. “She’s the real troublemaker. No need to be too gentle with her.”

That phrase echoes through my head “No need to be too gentle.” That seems like a lot for just trying to be heard—for wanting to vote. And the way the doctor put it makes me wonder if he even noticed that I’m a woman too.

When I walk past the cell, she looks up—and something in my chest jolts. Not fear. Not pity. Just the sudden awareness that I’ve been seen.

She hasn’t eaten in four days.

I’m new here. From a city hospital in D.C. They said Occoquan needed someone calm under pressure. I thought I’d be dressing wounds. Maybe stitching cuts. I didn’t think I’d be holding a woman’s head still while a tube was forced down her nose because they don’t want martyrs and this woman refuses to eat.

This wasn’t in the training manual.

They put me on midnight rounds. Quieter hours. Fewer reporters. Fewer eyes. Just cold stone, wheezing women, and footsteps that echo longer than they should.

She doesn’t wheeze. Doesn’t cry. Doesn’t scream.

That’s what makes her different.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Bathroom Breaks & Bedtime Tales to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.